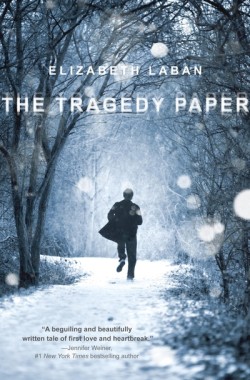

The Tragedy Paper

Boarding schools always make great settings for YA novels predominantly because of a distinct lack of adults (and more to the point parents!) and much like many a bildungsroman before it, The Tragedy Paper makes use of the device to explore what it means to be an ‘outsider’ and the meaning of tragedy. The setting, in this case, feels underused, particularly for a novel in which academic pressure is a central part of the narrative; though Tim and Duncan are both seniors, the novel gives the impression of a remarkably easy school life – there’s no mention of homework whatsoever. Talk about wish fulfilment!

The Tragedy Paper takes on two perspectives – that of Duncan, in the third person, and that of Tim, in the first. Whilst we are introduced to Duncan first, it is Tim’s narrative which dominates the novel and renders Duncan’s short chapters completely unnecessary – they only hold the novel back, particularly as LaBan finds it necessary to open each of Tim’s chapters with a paragraph of Duncan’s inconsequential and tedious thoughts. In fact, Duncan as a character should have been cut altogether as he serves little more than to frame Tim’s confession, which could as easily have stood on its own.

I was most disappointed by the characterisation in The Tragedy Paper, which is hideously underdeveloped. Tim makes a passable protagonist, his narrative and fall from grace at least interesting, even if he fawns over Vanessa in every paragraph. Vanessa, for the record, is one of the worst female characters I have ever read, due largely to her unjustified and unexplained relationship with Patrick, who she seems to detest but never breaks up with even though she seems to be a confident and strong-minded young woman. I’m sure LaBan has a good reason for this – but it’s never made public and so Vanessa just becomes an annoyance rather than the “forbidden love” that is so expectantly described in the synopsis. Patrick, too, is a completely one dimensional antagonist, and Duncan and Daisy’s relationship is completely and utterly unbelievable. Even Mr Simon, who I suspect is meant to be fulfil the “wonderfully insightful and inspiring teacher” role so frequently abused in coming-of-age literature, is mediocre at best, possessing all of the pretentiousness (his mantra is something like ‘go forth and spread beauty and light’) and none of the profundity of Mr Keatings from The Dead Poets’ Society.

The driving force of the novel is its sense of inevitability that at some point, something terrible will happen. Unfortunately, the tragedy, when it finally occurs, is entirely disappointing and anticlimactic; in part because of the lack of character development but also because it seems a little tedious and, to put it bluntly, not all that tragic. The fact that Tim feels a semblance of self-pity when it is entirely his fault doesn’t help, and neither does Duncan’s breakdown, which is as emotionally hard-hitting as an egg being dropped.

The Tragedy Paper has been unfairly compared to John Green’s Looking for Alaska, which is a far more competent and better-written novel about tragedy. Ultimately, The Tragedy Paper is based on a good idea but lacks emotional engagement with the characters, which are the foundations of any bildungsroman.