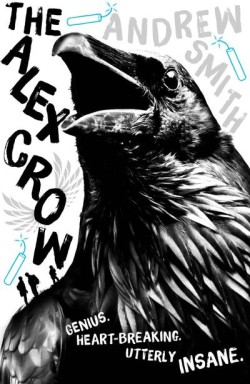

The Alex Crow

In 2014, Andrew Smith had his breakthrough year. The publication of Grasshopper Jungle, critically acclaimed and universally loved, and subsequent news of an adaptation process involving Edgar Wright of The Cornetto Trilogy fame, meant that all eyes were watching his next output. Publication in the UK of the brilliant Winger, from his US back catalogue, didn’t help. So 2015 is officially Andrew’s killer year: the year to make or break expectations. I don’t envy him.

Four stories collide in this tale of brotherhood, invasive spying, crazy science and war. Ariel and his adopted American brother Max attend Camp Merrie Seymour for Boys: a six week summer camp for the technologically addicted. Together with their new friend Cobie Petersen, they are pretty much the three only normal teenage boys; sent because their parents work for the Alex Division, a super-secret inventive science corporation that specialises in resurrecting extinct animals and proclaiming the end for the male race. Why have they been sent there? Who is the man driving through West Virginia who is getting progressively more addled, and what does this all have to do with a polar voyage in the 19th century?

Structurally, The Alex Crow returns to Smith’s fractal storytelling found in Grasshopper Jungle. Overall, there’s less of it – less repetition, less individual stories, less giant insects. Less wacky? Not so much – there’s still plenty of Andrew’s bizarre ideas – and, of course, the limitless sex drive of teenage boys.

Yet it’s this wackiness that undermines The Alex Crow’s core narrative: of refugee Ariel, his countless lives and blossoming brotherhood with his adopted American family. Stories of biodrones, male extinction and the resurrection of creatures feel tacked on; they achieve little emotional resonance as we hear more of Ariel’s own story as a refugee in an unnamed (middle-eastern?) country. Smith’s usual inventiveness, normally a delight in its own right, feels out of place in The Alex Crow. There’s a sense that the novel could have done with a little more rigorous and critical editing: the power of the novel lies in its presentation of the “normal” world; the escapades of Max, Ariel and Cobie at Camp Merrie-Seymour for Boys. As it is, too much page time is squandered by the journals of a polar voyage in the late 1800s and the deterioration of the “melting man”, Leonard, without effect on what The Alex Crow is really about.

That said, there’s a lot to like about The Alex Crow; yet it’s hard to escape the feeling of knowing that it could have been a far, far better piece of storytelling; one with less of Andrew’s wonderfully bonkers ideas, with greater focus on the human – and very normal – story of brotherhood. As one of the weaker entries in the Andrew Smith canon it still bares reading – if only for the current exploration of what it means to be a refugee in a war-torn country, but if you’re really picky I’d go for Winger or the aforementioned Grasshopper Jungle.